Uranium Resources in New Mexico

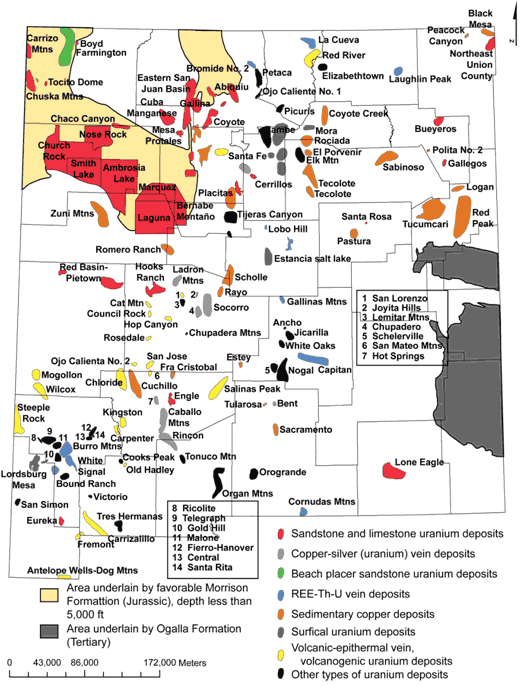

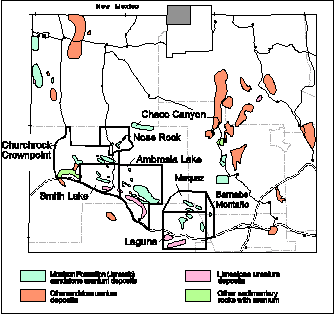

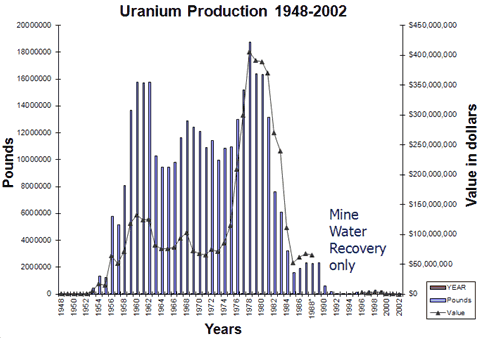

During a period of nearly three decades (1951-1980), the Grants uranium district in northwestern New Mexico (Figs. 1, 2, 3) yielded more uranium than any other district in the United States (Table 1; also see spreadsheet, McLemore, 1989, table 1). Although there are no producing operations in the Grants district today, numerous companies have acquired uranium properties and plan to explore and develop deposits in the district in the future. The Grants district is a large area in the San Juan Basin, extending from east of Laguna to west of Gallup, and includes eight subdistricts (Fig. 2; McLemore and Chenoweth, 1989; McLemore et al., 2013). The Grants district is probably 7th in total world production behind East Germany, Athabasca Basin in Canada, Australia, South Africa, Russia, and Kazakhstan (Tom Pool, General Atomics, Denver, Colorado, written communication, August 16, 2011). Most of the uranium production in New Mexico has come from the Jurassic Morrison Formation in the Grants district in McKinley and Cibola (formerly Valencia) Counties, mainly from the Westwater Canyon Member in the San Juan Basin (Tables 2, 3; McLemore, 1983). Other areas outside of the Grants district in New Mexico have been examined for uranium potential and some of these areas yielded minor production (Fig. 1; McLemore, 1983; McLemore and Chenoweth, 1989). A few of these areas are being examined again today for their economic potential. Major uranium deposits in New Mexico are shown in McLemore et al. (2013) and in a spreadsheet in an associated data repository and table.

| TYPE OF DEPOSIT | PRODUCTION (LBS U3O8) | PERIOD OF PRODUCTION (YEARS) | PRODUCTION TOTAL IN NEW MEXICO (PERCENT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary, redistributed, remnant sandstone uranium deposits (Morrison Formation, Grants district) | 330,453,000 | 1951-1988 | 95.4 |

| Mine-water recovery (Morrison Formation, Grants district) | 9,635,869 | 1963-2002 | 2.4 |

| Tabular sandstone uranium deposits (Morrison Formation, Shiprock district) | 493,510 | 1948-1982 | 0.1 |

| Other Morrison Formation sandstone uranium deposits (San Juan Basin) | 991 | 1955-1959 | — |

| Other sandstone uranium deposits (San Juan Basin) | 503,279 | 1952-1970 | 0.1 |

| Limestone uranium deposits (Todilto Limestone; predominantly Grants district) | 6,671,798 | 1950-1985 | 1.9 |

| Other sedimentary rocks with uranium deposits (total NM) | 34,889 | 1952-1970 | — |

| Vein-type uranium deposits (total NM) | 226,162 | 1953-1966 | — |

| Igneous and metamorphic rocks with uranium deposits (total NM) | 69 | 1954-1956 | — |

| Total in New Mexico | 348,019,000 | 1948-2002 | 100 |

| Total in United States | 927,917,000 | 1947-2002 | 37.5 of total US |

TABLE 2. Classification of uranium deposits in New Mexico (modified from McLemore and Chenoweth, 1989; McLemore, 2001; International Atomic Energy Agency, 2009). Deposit types in bold are found in the Grants uranium district.

- Peneconcordant uranium deposits in sedimentary host rocks

- Morrison Formation (Jurassic) sandstone uranium deposits

- Primary, tabular sandstone uranium-humate deposits in the Morrison Formation

- Redistributed sandstone uranium deposits in the Morrison Formation

- Remnant sandstone uranium deposits in the Morrison Formation

- Tabular sandstone uranium-vanadium deposits in the Salt Wash and Recapture Members of the Morrison Formation

- Other sandstone uranium deposits

- Redistributed uranium deposits in the Dakota Sandstone (Cretaceous)

- Roll-front sandstone uranium deposits in Cretaceous and Tertiary sandstones

- Sedimentary uranium deposits

- Sedimentary copper deposits

- Beach placer sandstone uranium deposits

- Limestone uranium deposits

- Limestone uranium deposits in the Todilto Limestone (Jurassic)

- Other limestone deposits

- Other sedimentary rocks with uranium deposits

- Carbonaceous shale and lignite uranium deposits

- Surficial uranium deposits

- Calcrete

- Playa lake deposits

Fracture-controlled uranium deposits

- Vein-type uranium deposits

- Copper-silver (±uranium) veins (formerly Jeter-type, low-temperature vein-type uranium deposits and La Bajada, low-temperature uranium-base metal vein-type uranium deposits)

- Collapse-breccia pipes (including clastic plugs)

- Volcanic epithermal veins

- Laramide veins (polymetallic veins)

- Disseminated uranium deposits in igneous and metamorphic rocks

- Igneous and metamorphic rocks with disseminated uranium deposits

- Pegmatites

- Alkaline rocks

- Granitic rocks

- Carbonatites

- Caldera-related volcanogenic deposits

- Miscellaneous

- Other types of uranium deposits

- Iron Oxide-Cu-Au (IOCG) (Olympic Dam deposits)

- Quartz Pebble conglomerate deposits

- By-product copper processing

| DISTRICT | PRODUCTION (lbs U3O8) | GRADE (U3O8%) | PERIOD OF PRODUCTION | TYPES OF DEPOSITS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grants district | ||||

| 1. Laguna | >100,600,000 | 0.1-1.3 | 1951-1983 | A, C, E |

| 2. Marquez | 28,000 | 0.1-0.2 | 1979-1980 | A |

| 3. Bernabe Montaño | None | A | ||

| 4. Ambrosia Lake | >211,200,000 | 0.1-0.5 | 1950-2002 | A, B, C, E |

| 5. Smith Lake | >13,000,000 | 0.2 | 1951-1985 | A, C |

| 6. Church Rock-Crownpoint | >16,400,000 | 0.1-0.2 | 1952-1986 | A, B |

| 7. Nose Rock | None | A | ||

| 8. Chaco Canyon | None | A | ||

| Shiprock district | ||||

| 9. Carrizo Mountains | 159,850 | 0.23 | 1948-1967 | A |

| 10. Chuska Mountains | 333,685 | 0.12 | 1952-1982 | A, C, B |

| 11. Tocito Dome | None | A | ||

| 12. Toadlena | None | B | ||

| Other areas and districts | ||||

| 13. Zuni Mountains | None | B, E, F | ||

| 14. Boyd prospect | 74 | 0.05 | 1955 | B |

| 15. Farmington | 3 | 0.02 | 1954 | B |

| 18. Chama Canyon | None | B | ||

| 19. Gallina | 19 | 0.04 | 1954-1956 | B |

| 20. Eastern San Juan Basin | None | B | ||

| 21. Mesa Portales | None | B | ||

| 22. Dennison Bunn | None | A | ||

| 23. La Ventana | 290 | 0.63 | 1954-1957 | D |

| 24. Collins-Warm Springs | 989 | 0.12 | 1957-1959 | A |

| 25. Ojito Spring | None | A | ||

| 26. Coyote | 182 | 0.06 | 1954-1957 | B, C |

| 27. Nacimiento | None | B | ||

| 28. Jemez Springs | None | B |

New Mexico has world class uranium deposits in the Grants district and ranks 2nd in uranium reserves in the United States, which amounts to 64 million short tons of ore at 0.14% U3O8 (179 million pounds U3O8) at $50/lb (according the the U.S. Department of Energy). However, approximately 409 million pounds of uranium resources remain in the Grants district as identified by companies in the 1980s and recent exploration that were never mined (McLemore, 2007; McLemore et al., 2013; table). The most important deposits in the state are within sandstones of the Morrison Formation (Jurassic) in the Grants uranium district. More than 340 million pounds of U3O8 have been produced from Morrison deposits from 1948-2002 (Tables 1, 3), accounting for 97% of the total production in New Mexico and more than 30% of the total production in the U.S. Sandstone uranium deposits are defined as epigenetic concentrations of uranium in fluvial, lacustrine, and deltaic sandstones (Fig. 4).

Three types of sandstone uranium deposits are recognized in the Grants district: tabular (primary, trend, blanket, black-band), roll-front (redistributed, post-fault, secondary), and fault-related (redistributed, stack, post-fault). Several companies are planning to mine some of these deposits by in-situ leaching. Other areas outside of the Grants district in New Mexico have been examined for uranium potential and some of these areas yielded minor production.

Sandstone and limestone uranium deposits in New Mexico have played a major role in historical uranium production. Although worldwide other types of uranium deposits are higher in grade and larger in tonnage, the Grants uranium district has been a significant source of uranium and has the potential to become an important future source, as low-cost technologies, such as insitu leaching techniques improve, and as demand for uranium increases, increasing the price of uranium.

The advantages of uranium resources in the Grants districts include:

- Major mining companies abandoned the districts after the last cycle leaving advanced uranium projects, see Table.

- Inexpensive property acquisition costs include millions of dollars of exploration and development expenditures already incurred during the 1970s and 1980s exploration cycle.

- Availability of data and technical expertise.

- Recent advances in in situ leaching makes sandstone uranium deposits attractive economically (McLemore et al., 2016).

However, several challenges need to be overcome by mining companies before uranium could be produced once again from the Grants uranium district and elsewhere from New Mexico:

- No conventional mills remain in New Mexico to process the ore, adding to the cost of producing uranium in the state. Currently all conventional ore must be processed by the White Mesa Mill near Blanding, Utah, or heap leached on site. New infrastructure will need to be built before conventional mining can resume.

- Permitting for new insitu leaching, especially for conventional mines and mills, will take years to complete.

- Closure plans, including reclamation, must be developed before mining or leaching begins. Modern regulatory costs will add to the cost of producing uranium in the U.S.

- Some communities, especially the Navajo Nation communities, do not view development of uranium properties as favorable. The Navajo Nation has declared that no uranium production will occur on tribal lands. Most of Mt. Taylor and adjacent mesas have been designated as the Mt. Taylor Traditional Cultural Property; the effect of this designation on uranium exploration and mining is uncertain.

- High-grade, low-cost uranium deposits in Canada and Australia and the large low-grade deposits in Kazakhstan are sufficient to meet current international demands; additional resources will be required to meet long-term future requirements.

Also see McLemore Uranium page for information on uranium research!

For a more detailed summary see Memoir 50C.

ADDITIONAL READING

- Anderson, O.J., 1980, Abandoned or inactive uranium mines in New Mexico: New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, Open-file Report OF-148, 778 p.

- Chamberlin, R.M., 1981, Uranium potential of the Datil Mountains-Pie Town area, Catron County, New Mexico: New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, Open-file Report OF-138, 58 p.

- Chenoweth, W.L., 1985a, Historical review of uranium production from the Todilto Limestone, Cibola and McKinley Counties, New Mexico: New Mexico Geology, v. 7, p. 80-83.

- Chenoweth, W.L., 1985b, Raw materials activities of the Manhattan Project in New Mexico: New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, Open-file Report OF-241, 12 p.

- Chenoweth, W.L., 1989a, Geology and production history of uranium deposits in the Dakota Sandstone, McKinley County, New Mexico: New Mexico Geology, v. 11, p. 21-29.

- Energy Information Administration, 2010, U.S. Energy Reserves by state: U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration (accessed July 11, 2010).

- Hilpert, L.S., 1969, Uranium resources of northwestern New Mexico: U.S. Geological Survey, Professional Paper 603, 166 p.

- International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), 2009, World distribution of uranium deposits with uranium deposit classification: IAEA Report IAEA-TECDOC-1629, 126 p. (accessed 11/25/13).

- McLemore, V. T., 1983, Uranium and thorium occurrences in New Mexico: distribution, geology, production, and resources; with selected bibliography: New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, Open-file Report OF-183, 950 p., also U.S. Department of Energy, Report GJBX-11(83).

- McLemore, V. T., 2001, Silver and gold resources in New Mexico: New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, Resource Map 21, 60 p.

- McLemore, V.T., 2007, Uranium resources in New Mexico: Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration Inc., Annual Convention, Denver, Feb 2007, Preprint 07-111.

- McLemore, V.T., 2009, In-situ recovery of sandstone uranium deposits in New Mexico: Past, present, and future issues and potential: Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration Inc., Annual Convention, Denver, Feb 2009, Preprint 09-21.

- McLemore, V.T., 2010, Use of the New Mexico Mines Database and ArcMap in uranium reclamation studies: Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration Transactions, 10 p.

- McLemore, V.T., 2010b, Use of the New Mexico Mines Database and ArcMap in uranium reclamation studies: Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration Inc., Annual Convention, Phoenix, Feb 2010, Preprint 10-125, https://geoinfo.nmt.edu/staff/mclemore/documents/10-125.pdf.

- McLemore, V.T., 2011, The Grants uranium district: Update on source, deposition, exploration: The Mountain Geologist, v, 48, p. 23-44.

- McLemore, V.T., 2013, National Uranium Resource Evaluation Data (NURE):< https://geoinfo.nmt.edu/libraries/nure/home.html >

- McLemore, V.T. and Chenoweth, W.L., 1989, Uranium resources in New Mexico: New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Minerals Resources, Resource Map 18, 36 p.

- McLemore, V.T. and Chenoweth, W.L., 1991, Uranium mines and deposits in the Grants district, Cibola and McKinley Counties, New Mexico: New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, Open File Report OF-353, 22 p.

- McLemore, V.T. and Chenoweth, W.C., 2017, Uranium resources; in McLemore, V.T., Timmons, S., and Wilks, M., eds., Energy and Mineral deposits in New Mexico: New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources Memoir 50 and New Mexico Geological Society Special Publication 13, 80 p.

- McLemore, V.T., Donahue, K., Krueger, C.B., Rowe, A., Ulbricht, L., Jackson, M.J., Breese, M.R., Jones, G., and Wilks, M., 2002, Database of the uranium mines, prospects, occurrences, and mills in New Mexico: New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, Open file Report OF-461.

- McLemore, V.T., Hill, B., Khalsa, N., and Lucas Kamat, S.A., 2013, Uranium resources in the Grants uranium district, New Mexico: An update: New Mexico Geological Society, Guidebook 64, p. 117-126.

-

McLemore, V.T., Wilton, T., and Pelizza, M., 2016, In-Situ Recovery of Sandstone-Hosted Uranium Deposits in New Mexico: Past, Present, and Future Issues and Potential: New Mexico Geology, v. 38, no. 4, p. 68-76.

Updated January 27, 2020